R is a programming language for statistical computing. It currently ranks as the 12th most popular language in use today.

R's focus is on statistics, data manipulation and visualization. It has a flourishing, friendly community supporting it with thousands of open-source add-ons (‘packages') with a particular lean towards data science and analytics.

R is free, and available from the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). This article will use R version 4.1.

For developing code and managing your data science projects, I highly recommend the open source RStudio which provides an excellent integrated development environment (IDE).

If you'd like to avoid all the bother of installing R and RStudio, you can try them both out for free on the web using RStudio CLoud, where you can program right inside your browser.

Within R Studio, you are provided with a console where you can type R commands directly and then see the results.

Within this console, try typing a simple sum and observe the results like so,

1+2

[1] 3

Notice R prints the correct answer 3 to the console, with a bracketed element number [1].

In R, all results are returned as vectors, which can contain multiple values. You can combine multiple values into a longer vector using the c() function,

c(1,2,3)

[1] 1 2 3

Assignment

To store a vector inside of a named variable, R uses the <- operator. For example, to store the character vector "Hello, World!" in a variable called welcome, you would type this,

welcome <- "Hello, World!"

To see the values stored in your welcome variable, you can use the print() function.

print(welcome)

[1] "Hello, World!"

Element Addresses

When storing multiple values in a vector, you may wish to subset that vector and access single or a subset of elements within it.

Lets set up a character vector called fruit

fruit <- c("Apple", "Pear", "Orange")

print(fruit)

[1] "Apple" "Pear" "Orange"

To access elements within the vector, we use the [_index] operator. In R, unlike in python, the index of the vector starts at 1 (Python starts at 0). So to access the second element you would type,

fruit[2]

[1] "Pear"

Data Frames

So far, we have just dealt with 1-dimensional vectors, but in data science we most often deal with tabulated data (like a spreadsheet) with rows and columns.

The data.frame object is the best way to create or store such tabular data. Lets create a few more variables and also a fruit_shop data frame.

fruit_colour <- c("Green", "Green", "Orange")

fruit_price <- c(0.30, 0.50, 0.75)

fruit_shop <-

data.frame(

fruit_type = fruit,

fruit_colour = fruit_colour,

fruit_price = fruit_price

)

print(fruit_shop)

fruit_type fruit_colour fruit_price

1 Apple Green 0.30

2 Pear Green 0.50

3 Orange Orange 0.75

Notice R ignores white space so you're free to break up code into multiple lines to help readability.

To access individual elements of a 2D object such as a data.frame, you can use the same operator [] specifying the rows and columns [row, column]

fruit_shop[1,3]

[1] 0.3

To choose a single column but all the rows, just omit the index for the row,

fruit_shop[,2]

[1] "Green" "Green" "Orange"

For a range of values, you can use the shorthand n:m which produces a vector of integers from n to m inclusive,

fruit_shop[1:2,] # First two rows, all columns

fruit_type fruit_colour fruit_price

1 Apple Green 0.3

2 Pear Green 0.5

Data wrangling in R is the process of importing, analyzing, cleaning and summarizing data. In this section we will take a look at a sample dataset contaning aircraft flights from NYC.

For this section you will need to install the nycflights13 package, which contains the data, and the dplyr package for data manipulation.

You can install both these packages with the following command,

install.packages(c("dplyr", "nycflights13"))

We will the load these packages into our R session

Attaching package: 'dplyr'

The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

filter, lag

The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

And we can take a look at the flights data by printing it to the console

print(flights)

# A tibble: 336,776 x 19

year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

<int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

5 2013 1 1 554 600 -6 812 837

6 2013 1 1 554 558 -4 740 728

7 2013 1 1 555 600 -5 913 854

8 2013 1 1 557 600 -3 709 723

9 2013 1 1 557 600 -3 838 846

10 2013 1 1 558 600 -2 753 745

# ... with 336,766 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

# carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

# air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>

Although flights is a type of data frame, the output to the console is much neater than normal. This is because flights is actually a type of data frame called a tibble. The distinction doesn't make any practical difference to our analysis, for our needs it just prints tidier output to the console.

Selecting and Filtering

With dplyr, we can select a subset of columns using the select function. Lets select the month and the year from the dataset like so,

select(.data = flights, month, year)

# A tibble: 336,776 x 2

month year

<int> <int>

1 1 2013

2 1 2013

3 1 2013

4 1 2013

5 1 2013

6 1 2013

7 1 2013

8 1 2013

9 1 2013

10 1 2013

# ... with 336,766 more rows

We can also use dplyrs filter() function to filter the results to some logcial condition. For example, we can filter to only flights in January like so,

filter(.data = flights, month == 1)

# A tibble: 27,004 x 19

year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

<int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

5 2013 1 1 554 600 -6 812 837

6 2013 1 1 554 558 -4 740 728

7 2013 1 1 555 600 -5 913 854

8 2013 1 1 557 600 -3 709 723

9 2013 1 1 557 600 -3 838 846

10 2013 1 1 558 600 -2 753 745

# ... with 26,994 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

# carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

# air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>

Pipes

Say we wanted to combine the last two steps to both selecitng only a few columns and then filtering. TO achieve this, we could write,

filter(select(.data = flights, month, year), month == 1)

# A tibble: 27,004 x 2

month year

<int> <int>

1 1 2013

2 1 2013

3 1 2013

4 1 2013

5 1 2013

6 1 2013

7 1 2013

8 1 2013

9 1 2013

10 1 2013

# ... with 26,994 more rows

However, you can see that this isn't very human-readable. It's not too clear what exactly is happening, or what steps are performed in what order. You can imagine with complex data wrangling, this way of writing code will soon become unreadable and hard to maintain.

This is where the pipe operator (%>%) comes in handy. The pipe takes the result of the expression on the left hand side and passes it as the first argument to the right hand side. So the same set of calls becomes,

flights %>%

select(month, year) %>%

filter(month == 1)

# A tibble: 27,004 x 2

month year

<int> <int>

1 1 2013

2 1 2013

3 1 2013

4 1 2013

5 1 2013

6 1 2013

7 1 2013

8 1 2013

9 1 2013

10 1 2013

# ... with 26,994 more rows

Here we take flights and pipe it to the select() function. The first argument for select is .data = so flights is passed as this parameter. Within dplyr, all the data functions accept .data = first, so the pipe is extremely powerful to chain commands together.

Mutate

To mutate a data.frame is to change it by adding an additional column. The data for this new column can be a new vector, or it can be some calculation / operation on existing columns.

Lets add a column called distance_km than converts the distance column (in miles) to a distance in kilometers,

flights %>%

select(carrier, distance) %>%

mutate(distance_km = 1.61 * distance)

# A tibble: 336,776 x 3

carrier distance distance_km

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 UA 1400 2254

2 UA 1416 2280.

3 AA 1089 1753.

4 B6 1576 2537.

5 DL 762 1227.

6 UA 719 1158.

7 B6 1065 1715.

8 EV 229 369.

9 B6 944 1520.

10 AA 733 1180.

# ... with 336,766 more rows

Summarise

We may also want to summarise data by performing some aggregations on the data. For this, we use the summarise() function.

flights %>%

select(carrier, distance) %>%

mutate(distance_km = 1.61 * distance) %>%

summarise(avg_distance = mean(distance_km))

# A tibble: 1 x 1

avg_distance

<dbl>

1 1674.

In this case, we summarise all the rows to find the mean distance in kilometers for the whole dataset.

Groups

So far, we have selected, filtered and summarised the flights dataset as a whole. However, we may wish to perform these operations on groups of data within the dataset.

For example, what is the average distance per company? dplyr lets you group the dataset based on one or more of it's columns, and then all subsequent ooperations will be done group-by-group.

As an example, lets get the mean distance per carrier,

flights %>%

select(carrier, distance) %>%

mutate(distance_km = 1.61 * distance) %>%

group_by(carrier) %>%

summarise(avg_distance = mean(distance_km))

# A tibble: 16 x 2

carrier avg_distance

<chr> <dbl>

1 9E 854.

2 AA 2158.

3 AS 3867.

4 B6 1720.

5 DL 1991.

6 EV 906.

7 F9 2608.

8 FL 1070.

9 HA 8023.

10 MQ 917.

11 OO 806.

12 UA 2462.

13 US 891.

14 VX 4024.

15 WN 1604.

16 YV 604.

Base Plotting

R's inbuilt plot() function can create visualizations of your data. It's pretty good, but you should be aware there are some far more powerful graphing options available via packages that we'll cover later.

Lets plot a data frame. R has some in-built data sets that are really useful for quick experiments. Lets try plotting one of these in-built data frames, the Orange data set. This data set contains observations of several Orange trees over time, and their trunk circumference. We can take a look by printing the Orange data set to the console.

Orange

Tree age circumference

1 1 118 30

2 1 484 58

3 1 664 87

4 1 1004 115

5 1 1231 120

6 1 1372 142

7 1 1582 145

8 2 118 33

9 2 484 69

10 2 664 111

11 2 1004 156

12 2 1231 172

13 2 1372 203

14 2 1582 203

15 3 118 30

16 3 484 51

17 3 664 75

18 3 1004 108

19 3 1231 115

20 3 1372 139

21 3 1582 140

22 4 118 32

23 4 484 62

24 4 664 112

25 4 1004 167

26 4 1231 179

27 4 1372 209

28 4 1582 214

29 5 118 30

30 5 484 49

31 5 664 81

32 5 1004 125

33 5 1231 142

34 5 1372 174

35 5 1582 177

We see this data frame has three columns, a Tree id that identifies which tree, the age of the tree (in days), and the tree's circumfrance. Tosee information on the data set, or indeed any function, you can quickly bring up the help by typing ?Orange.

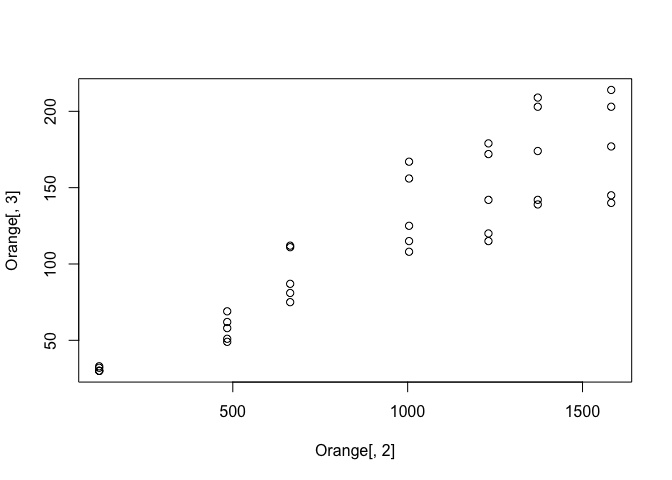

Lets plot this data frame so see the relationship between age and circumfrance. For this we'll select column 2 for the x-axis and column 3 for the y axis.

plot(Orange[,2], Orange[,3])

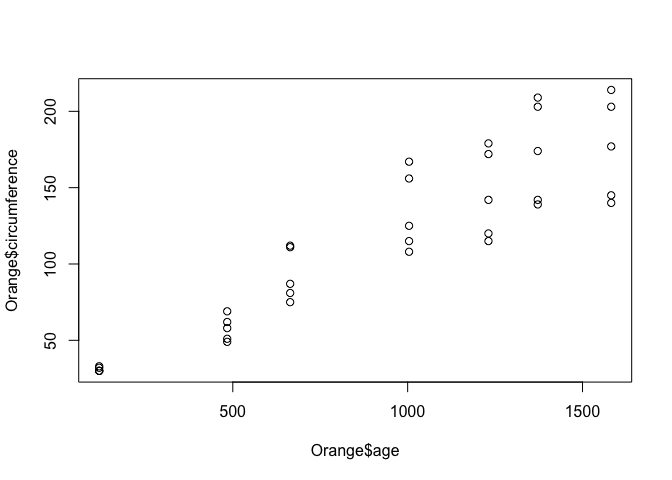

Not a bad start, but we can do better. Firstly, lets make our code more readable by using a different way of selecting columns.

For data frames, we can use the $ operator to refer to a column by it's name, rather than it's index.

plot(Orange$age, Orange$circumference)

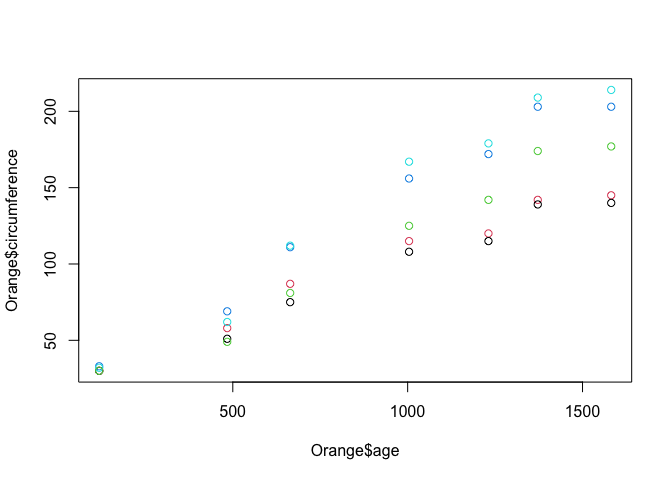

Ok, not much change to the graph, except the axis labels are a little more helpful. Now, lets colour the points by the tree which the observation came from. We do this by passing the col = parameter to the plot() function.

plot(Orange$age, Orange$circumference, col = Orange$Tree)

There are lots of other base plotting functions in R, such as barplot(), boxplot() and hist(). However, the majority of data scientists forego the base plotting in favor of an open source alternative called ‘ggplot'.

ggplot

The ggplot package stands for the grammar of graphics plots. It's design is based on a book by Leland Wilkinson called, unsurprisingly, The Grammar of Graphics. It was created by Hadley Wickham, who is now the chief data scientist as RStudio, and is one of the R community's most prolific contributors.

To use a package, we must first install it. To install packages into R, you use the install_packages() function.

install.packages("ggplot2")

We then need to load a package into our R session, which we do like so,

library(ggplot2)

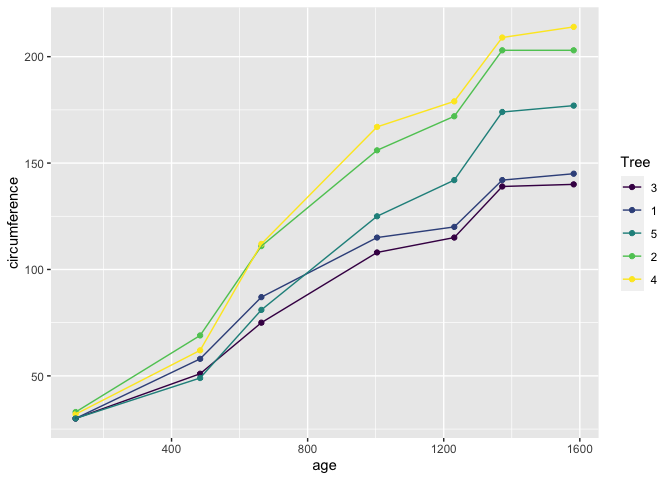

Lets explore how ggplot works. The philosophy of ggplot is that a plot is made of elements that should be separately controlled. We have things like the scales on the axis, the geometries we use to represent the data (such as points for scatter plots, lines for trends or bars for barcharts),

Lets start by plotting our Oranges,

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(data = Orange, mapping = aes(x = age, y = circumference, colour = Tree)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line()

Lets break down this bit of code.

- In the first line of this call, the first argument we pass to

ggplot()is always the data, the second argument wrapped in theaes()function are called the aesthetics, which define how the data is mapped to elements of the chart. - We've mapped here the

xvalues toage, theyvalues tocircumference, and thecolourvalues to theTree. (The american spellingcolor=is also acceptable). - In the subsequent lines, we have added using the

+operator different geometries to represent our data, such as points and lines. These points and lines inherit the aesthetics, so they know what x, y, and colour values they should be using to be consistent with the data.

ggplot is far more powerful that base graphics when plotting complex charts thanks to this simple separation between the data and the chart elements.

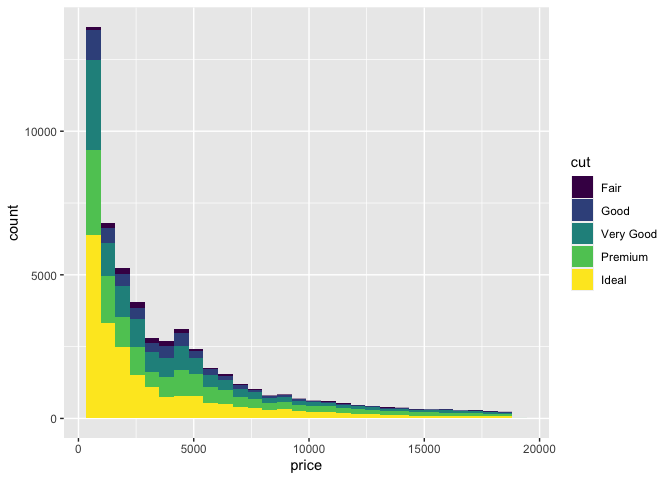

Lets try a more complex examples using the example data set from ggplot, diamonds.

ggplot(

data = diamonds,

mapping = aes(

x = price,

fill = cut

)

) +

geom_histogram()

`stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

In this example, we mapped the price of a set of diamonds to x, and the fill colour to the quality of the diamond's cut. We then added a histogram geometry to get the resulting histogram plot.

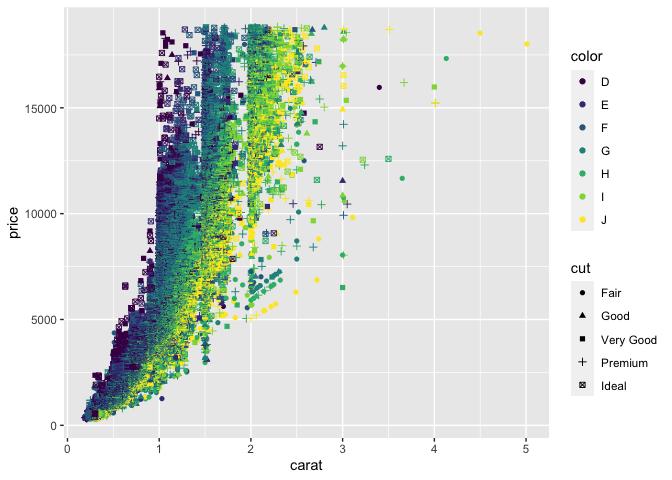

Lets try mapping other aesthetics,

ggplot(

data = diamonds,

mapping = aes(x = carat, y = price, color = color, shape = cut)

) +

geom_point()

Warning: Using shapes for an ordinal variable is not advised

Here we've mapped x, y, shape, colour and the quality of cut to various aesthetics that have then been used in the geom_point() geometry.

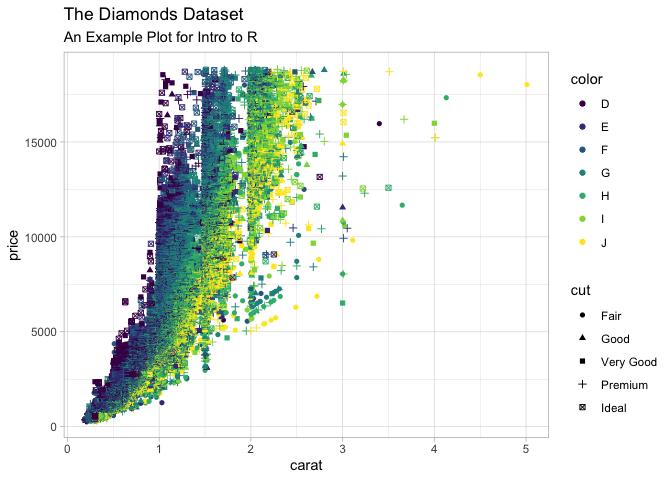

Lets just quickly this plot up by adding labels and a theme

ggplot(

data = diamonds,

mapping = aes(x = carat, y = price, color = color, shape = cut)

) +

geom_point() +

labs(

title = "The Diamonds Dataset",

subtitle = "An Example Plot for Intro to R",

) +

theme_light()

Warning: Using shapes for an ordinal variable is not advised

In this section we are going to demonstrate the machine learning capabilities of R using the tidymodels package.

The tidymodels package is relatively new, and is a ‘meta package' that wraps up lots of machine learning packages with a common API.

This makes switching between models and methods really easy, even if the underlying packages they are based on behave very differently. Most of this functionality is actually provided by a tidymodels package, parsnip.

Get the Data

Duration 15

For this simple example to demonstrate the power of ML in R, I have prepared and pre-processed some data for us. We will be using a prepossessed version of the palmerpenguins dataset.

The pre-processed versions we will be using can be downloaded from gitlab. There are two files, one for analysis/training the model, and one file of independent observations for assessment/testing the model.

Alternatively, and encouraged, you can load these files directly into R using their URLS like so

library(readr)

df_analysis <-

read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/tjconstant/penguins/main/penguins_analysis.csv") %>%

mutate(species = as.factor(species))

Rows: 258 Columns: 8

── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Delimiter: ","

chr (3): island, sex, species

dbl (5): bill_length_mm, bill_depth_mm, flipper_length_mm, body_mass_g, year

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.

df_assesment <-

read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/tjconstant/penguins/main/penguins_assessment.csv") %>%

mutate(species = as.factor(species))

Rows: 86 Columns: 8

── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Delimiter: ","

chr (3): island, sex, species

dbl (5): bill_length_mm, bill_depth_mm, flipper_length_mm, body_mass_g, year

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.

We have also changed the species column type to a factor rather than a character. Factors are useful for categorical types of data and is expected by most of tidymodels functions.

Choosing a Classifier

For starters, we are going to use a Decision Tree classifier to attempt to predict the species of the penguins based on the other variables.

To set up a classifier we will create a model object like this,

library(tidymodels, quietly = TRUE)

Registered S3 method overwritten by 'tune':

method from

required_pkgs.model_spec parsnip

── Attaching packages ────────────────────────────────────── tidymodels 0.1.3 ──

✓ broom 0.7.8 ✓ rsample 0.1.0

✓ dials 0.0.9 ✓ tibble 3.1.2

✓ infer 0.5.4 ✓ tidyr 1.1.3

✓ modeldata 0.1.1 ✓ tune 0.1.6

✓ parsnip 0.1.7 ✓ workflows 0.2.3

✓ purrr 0.3.4 ✓ workflowsets 0.1.0

✓ recipes 0.1.16 ✓ yardstick 0.0.8

── Conflicts ───────────────────────────────────────── tidymodels_conflicts() ──

x purrr::discard() masks scales::discard()

x dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

x dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

x yardstick::spec() masks readr::spec()

x recipes::step() masks stats::step()

• Use tidymodels_prefer() to resolve common conflicts.

classifier <-

decision_tree(mode = "classification") %>%

set_engine("rpart")

Note you may need to install rpart package for using the decision tree example above.

Fitting the Model

To fit the model, we call the fit command.

model <- fit(classifier, formula = species ~ ., data = df_analysis)

We specify the classifier (The Decision Tree). We also provide a formula telling the fit function what we are predicting and what to use as predictors. For this formula we specify the species column as the output, and use the shorthand species ~ . to indicate that everything else should be used as the predictors.

If we wanted to try and predict the species based solely on island and sex (a poor idea!), we would instead write species ~ island + sex.

Evaluate the model

We now assess the model based on data it has not previously seen, and deduce the accuracy of our model.

For this, we use our trained model to predict the species from the df_assessment data frame.

df_pred <- predict(model, new_data = df_assesment)

df_pred

# A tibble: 86 x 1

.pred_class

<fct>

1 Adelie

2 Adelie

3 Chinstrap

4 Adelie

5 Adelie

6 Adelie

7 Adelie

8 Adelie

9 Adelie

10 Adelie

# ... with 76 more rows

Notice only the predictions are returned in a single column names .pred_class. It will be more useful to have the original df_assessment appended, so instead we can bind the columns together using bind_cols.

df_pred <-

df_assesment %>%

bind_cols(

predict(model, new_data = df_assesment)

)

df_pred

# A tibble: 86 x 9

island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm flipper_length_... body_mass_g sex year

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

1 Torger... 40.3 18 195 3250 fema... 2007

2 Torger... 36.6 17.8 185 3700 fema... 2007

3 Torger... 46 21.5 194 4200 male 2007

4 Biscoe 35.9 19.2 189 3800 fema... 2007

5 Biscoe 38.2 18.1 185 3950 male 2007

6 Biscoe 40.6 18.6 183 3550 male 2007

7 Dream 37.2 18.1 178 3900 male 2007

8 Dream 39.8 19.1 184 4650 male 2007

9 Dream 37 16.9 185 3000 fema... 2007

10 Dream 39.6 18.8 190 4600 male 2007

# ... with 76 more rows, and 2 more variables: species <fct>, .pred_class <fct>

To test the accuracy of this model, we can pass the resulting data frame to accuracy.

df_pred %>%

accuracy(truth = species, estimate = .pred_class)

# A tibble: 1 x 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 accuracy multiclass 0.953

Abut 95% accuracy! Not bad!

Improving the model

One of the great things about tidymodels (and under the hood parsnip), is the method of building the model is the same whichever model we try an run.

For example, instead of a decision tree, why don't we try a Random Forest?

The following code chunk is identical to the commands above, except for the classifer <- line. We also need to install the Random Forest library ranger before running this code.

classifier <-

rand_forest(mode = "classification") %>%

set_engine("ranger")

model <- fit(classifier, formula = species ~ ., data = df_analysis)

df_pred <-

df_assesment %>%

bind_cols(

predict(model, new_data = df_assesment)

)

df_pred %>%

accuracy(truth = species, estimate = .pred_class)

# A tibble: 1 x 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 accuracy multiclass 0.988

98%! Very good. Lastly (since it's so easy!), lets tre a Gradient Boosted tree. Again, this code is identical except for the classifier. For this classifier you need to install the xgboost library.

classifier <-

boost_tree(mode = "classification") %>%

set_engine("xgboost")

model <- fit(classifier, formula = species ~ ., data = df_analysis)

[11:26:43] WARNING: amalgamation/../src/learner.cc:1095: Starting in XGBoost 1.3.0, the default evaluation metric used with the objective 'multi:softprob' was changed from 'merror' to 'mlogloss'. Explicitly set eval_metric if you'd like to restore the old behavior.

df_pred <-

df_assesment %>%

bind_cols(

predict(model, new_data = df_assesment)

)

df_pred %>%

accuracy(truth = species, estimate = .pred_class)

# A tibble: 1 x 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 accuracy multiclass 1

100%!!!

OK, so any Data Scientist should be wary of perfect accuracy, and we should thoroughly check these models using techniques like cross-validation. But hopefully this gives you an idea of the power of tidymodels and parsnip.

There is lots of other features of tidymodels I haven't covered here like pre-processing using the recipies packages, building ML pipelines using workflow, Auto ML type analysis using workflowsets and all the different sampling and cross-validation techniques. But common to all these packages that are part of tidymodels is they follow a common API structure and can be swapped in and out with little changes to your code.